Written June 2024

The widespread emergence and integration of social media has revolutionised political campaigning, enabling unprecedented direct communication between politicians and the public, bolstered by advanced data analytics. Unfortunately, these tools are often wielded to propagate misinformation, manipulate voter behaviour, and reinforce ideological bubbles. This essay argues that social media has fundamentally reshaped the political landscape, exacerbating political polarisation within the United States, fuelled by partisan agendas exploiting these platforms for campaigning purposes. Consequently, societal cohesion and governance have suffered. While this has led to calls for censorship, this essay asserts that this is not an effective measure as it infringes upon freedom of speech. Instead, advocating for ethical standards and critical thinking can counteract social media's detrimental effects.

How social media changed political campaigning in the USA

The Social Media Era: Major platforms and their use in the USA

The history of social media's influence in the USA is marked by the rise of major platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. On a macro level, 39 per cent of Americans are using social media to engage in civic and political life, learning about issues and candidates, engaging in political and policy conversations; and influencing their personal networks on how to vote1. These platforms revolutionised communication by offering instant, widespread connectivity. Facebook, launched in 2004, quickly became a dominant social networking site, boasting over 2.8 billion monthly active users globally by 20212.Twitter, now called X, became a critical tool for real time information sharing and public discourse, especially in political contexts. This widespread adoption by the American public shows the significant role social media plays in everyday communication and the power it can have to influence when used for political engagement. The introduction of the Internet into American life in the 1990s profoundly transformed the media landscape. This new digital technology facilitated greater interaction between political candidates and the public, which had previously been much more challenging. Social media emerged from the Internet, enabling real time engagement with a much wider audience. Unlike traditional media, social media allows for real time interaction, enabling politicians to respond swiftly to current events and shape narratives to their advantage. This immediacy is crucial in modern politics, where public perception can shift rapidly.

Social Media as a Political Advocacy Tool

The introduction of social media enabled political mobilisation on an unprecedented scale. Grassroots movements, such as Black Lives Matter, have leveraged these platforms to organise protests, disseminate information, and build solidarity. Hashtags like #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter have become rallying cries, amplifying voices that might otherwise go unheard. The ability to mobilise large numbers of people quickly and effectively highlights social media's power as a tool for political activism3.

These movements have put pressure on regulators and governments, demonstrating the power of mobilising groups of individuals swiftly and effectively. Social media’s capacity to garnish public attention and catalyse social change highlights its significance in contemporary political advocacy.

The 2008 presidential election firmly established social media as a pivotal tool for political advocacy. Barack Obama's Democratic campaign notably leveraged social media to revolutionise political organisation, effectively turning his campaign into a social movement marked by robust digital grassroots mobilisation. This innovative strategy which involved engaging a younger audience who had integrated this technology into their everyday lives allowed for Obamas team to disseminate directed messages to a base of individuals in a way they wanted to be communicated with setting a new precedent for political campaigns.

The scholar Slotnick who wrote, ‘Friend the president- Facebook and the 2008 Presidential Election’, describes that Obama used his connection with Chris Hughes, who was integral in Facebooks founding, to build a networking site like Facebook which included some of the tradition forms of political mobilisation (events and fundraising) and finally toped them off with new media functions, such as running a blog. This site eventually became a one stop shop for any and all Obama campaign needs as it serviced his campaign and provided a tracking system for supporters and gave them tools at their fingers tips to create new networks and bring in additional supporters4.

Alternatively, Darrell West describes within, The History of Communications, the rise of Nanocasting and explains that social media, mobile technology, and geolocation devices that can pinpoint people’s specific location enabled the customisation and personalisation of campaign messaging. Using highly targeted ads on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Google, candidates can reach down to tiny niches based on dozens of people and seek to influence their voting behaviour 5.

Donald Trump's 2016 campaign notably utilised data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica to harness Facebook data for targeted political advertisements to voters. Cambridge Analytica accessed data from millions of Facebook users without their consent, creating psychological profiles to deliver personalised political ads designed to influence voter behaviour6. This scandal highlighted the powerful combination of social media and data analytics in political strategy, raising significant concerns about privacy, manipulation, and the ethical use of data. While it is apparent that the introduction of social media changed the way political campaigns where run and how voters’ data was collected and used this research confirms that it provided unprecedented opportunities for engagement and advocacy, however it also raised critical ethical concerns and cultural issues in regards to safeguarding democratic processes and societal cohesion

The misuse of social media for political purposes

Misinformation: Defining the Phenomenon

Misinformation, defined as false or misleading information, permeates multiple channels, including social media, traditional news outlets, and interpersonal communication7. It manifests in diverse formats, ranging from fabricated news articles and manipulated images to deceptive narratives aimed at distorting reality. Whether unintentional or deliberate, misinformation erodes public trust in institutions and the media and undermines the democratic process. Social media platforms, with their algorithm driven recommendation systems and emphasis on engagement metrics, serve as fertile breeding grounds for the spread of misinformation.

The anonymity afforded by these platforms enables the proliferation of fake accounts and automated bots, amplifying the reach and virality of false narratives8. Given the lack and access for the general public to use fact checking mechanisms this exacerbates the problem, allowing misinformation to be used for many purposes and to circulate in the public unchecked. Misinformation intensifies political polarisation by deepening existing ideological divides as it becomes easy to create narratives and conspiracy theories when ideals and facts are subjective and relatively hard to prove. Partisan bias drives individuals to seek out information that aligns with their preconceived beliefs, leading to the selective consumption and dissemination of misinformation. This polarisation not only impedes constructive dialogue but also undermines the foundational principles of democracy, as citizens retreat into tribalistic echo chambers.

Psychological Effects

If individuals base their decisions on either false or misleading information, it can have detrimental effects on society. This was evident in 2020 during the COVID-19 global pandemic when extreme views and information spread online while people were confined to their homes due to government regulation. The reliance on social media led to the dissemination of what some perceived as misinformation. This contributed to vaccine hesitancy and ultimately hampered efforts to contain the spread of more harmful strains of the virus, endangering public health and safety. The existing distrust in government and media facilitated the circulation of such information among segments of society already polarised by certain beliefs about institutions

Case Study: Misinformation being used for Political Purposes

The most notable instance of misinformation being used for extreme purposes during a political campaign took place during the 2021 election when Donald Trump fuelled and incentivised the Capitol Hill riot. This was driven by which later was revelled was baseless claims of voter fraud and election rigging, highlighting the real world consequences of unchecked misinformation and posing a direct threat to democratic norms and institutions. After losing the election, Donald Trump persistently conveyed to his audience, without any evidence, that the election was rigged and plagued by voter fraud. Some argue that this led to a culture of normalising political violence and inspiring further distrust within institutions and the media within the USA. Appendix 1 displays Trump's tweets from election day, illustrating how he communicated with his voter base and followers about the election, convincing them it was rigged9.

Political Polarisation & Social Medias impact

Political polarisation refers to the divergence of political attitudes to ideological extremes that is seen amongst voters in the USA. In political science, Polarisation is typically discussed in the context of political parties and democratic systems of government. In most countries that operate a two-party system, Polarisation embodies the tension between binary political

ideologies and partisan identities. Mass Polarisation, or popular Polarisation, occurs when an electorate’s attitudes towards political issues, policies, and celebrated figures are neatly divided along party lines. At its extreme, each camp questions the moral legitimacy of the other, viewing the opposing camp and its policies as existential threats to their way of life or the nation as a whole10.

In the 1950s, some influential U.S. scholars argued that America needed more Polarisation, which they defined as members of different parties holding differing policy beliefs. At the time, each of the two dominant parties encompassed a breadth of often overlapping political views due to conservative Southern Democrats and liberal Rockefeller Republicans. A famous American Political Science Review study from 1950 concluded that more Polarisation would help voters differentiate between the parties11.

More ideologically extreme politicians began running for office in greater numbers starting in the 1980s. Party chairs often selected and supported more extreme candidates, especially on the right. This trend suggests that parties and candidates believe that polarising figures are more likely to win elections.

This belief may become a self fulfilling prophecy: voters exposed to more polarising rhetoric from leaders who share their partisan identity are likely to alter their preferences based on their understanding of what their group believes and has normalised, particularly among primary voters whose identity is more tied to their party. Philanthropists and pro democracy organisations attempting to reduce polarisation often assume that the problem they must grapple with is polarised voters. Still, their interventions should also consider the fact that some of the ideological extremism and polarisation since the 1980s is candidate and party driven.

While candidates and parties may now be responding to Polarised primary voters, they have also been driving the Polarisation, and not all voters are ideologically polarised12. Subsequent sociopolitical changes influenced views on Polarisation. Well before social media was introduced into American lives polarisation was starting to take shape with the Civil Rights Movement and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which sent former Southern Democrats into the Republican Party, accelerating a process of party sorting by ideology largely influenced by racial prejudice. Cultural cleavages over women’s rights, gay rights, and the environment, combined with polarisation over the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal, continued the process of deepening ideological differences. Demographic sorting among the electorate put more liberals on the Democratic side and more conservatives on the Republican side. Politicians like Newt Gingrich amplified these cleavages in the 1990s through intensely partisan leadership, deepening the effects of these cultural and ideological differences on key institutions, particularly Congress13

The political landscape in the USA is now more sharply divided and intensely conflicted than in the past. This increasing polarisation impacts the functioning of democratic institutions and the political process itself. Political and ideological biases manifest in the sharp division between "red" states and "blue" states.

Appendix 2 shows graphs between 1994 to 2014 as well as different historical congresses that display that over time the division has gotten greater14. Social media has significantly altered political campaigning in the USA and has exacerbating the political issue of polarisation. As evident from this research around polarisation and its history it is evident that social media amplified this effect by providing a platform for partisan messages to spread rapidly, deepening ideological divides. Consequently, social media's role in campaigning has heightened polarisation, impacting the nation's democratic processes and cultural cohesion.

Allowing for the rise of misinformation represents a significant threat to democratic governance, societal cohesion, and cultural stability. It shows that misinformation can be formulated and used by those who run at the highest levels within our society which sets a benchmark and provide guidance for acceptable behaviour within the community. Given this misused social media has had a profoundly negative impact on political culture leading to many ongoing debates and legislative measures within the country’s political landscape.

Social Medias Impact on the Political & Legislative Landscape

As previously discussed, social medias used has led politicians to push for debate and legislation around greater censorship of these platforms. This response aims to curb the spread of misinformation and extreme partisan content, which are seen as major contributors to the growing polarisation and negative impact on the nation's political and cultural landscape. America prides itself on valuing freedom of speech, yet the nation has a history marked by intense battles to defend this right, as guaranteed by the First Amendment.

From the era of the Founding Fathers, the principle of free speech faced challenges, notably when President John Adams imposed restrictions on criticising government officials. This historical context sets the stage for the ongoing debate over content moderation on social media platforms. The First Amendment, adopted on December 15, 1791, as part of the Bill of Rights, explicitly protects freedom of speech and the press: "Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press..." 15. Censorship, defined by the US Supreme Court in Farmers Educational & Coop. Union v. WDAY, Inc. (1959) as "any examination of thought or expression in order to prevent publication of 'objectionable' material," implies that both private and public entities can infringe upon individual rights to freedom of speech16.

In the realm and day of social media used during campaigning the issue of censorship has reared its ugly head yet again. Because of political polarisation being pushed by candidates’ online platforms now grapple with misinformation, hate speech, and other harmful content, raising questions about the role of technology companies in regulating speech and content. Critics argue that censorship, whether by the government or private entities, is a lazy and ineffective solution to address these complex societal issues.

Case Studies in Content Moderation

➢ Facebook and Political Ads (2019): In 2019, Facebook faced significant backlash for its policy on political ads. The company decided not to fact-check political advertisements, arguing that it was not their role to interfere with political discourse. Critics argued that this policy allowed the spread of misinformation and false claims, potentially influencing voter perceptions and undermining the democratic process17. This debate highlights the challenge of finding a middle ground between upholding free speech and preventing the dissemination of false information in political contexts.

Entrusting technology companies with the task of fact-checking raises concerns, as it vests them with significant control over what gets published, potentially opening the door to misuse by their employees.

➢ Twitter and the Suspension of Donald Trump (2021): Following the January 6th 2021 Capitol riots, Twitter permanently suspended the account of then-President Donald Trump, citing the risk of further incitement of violence. This decision also sparked a heated debate over the role of social media platforms in regulating speech by political figures.

Supporters of the ban argued it was necessary to prevent further violence and misinformation, while opponents saw it as an overreach and a dangerous precedent for censorship18. This poses the question that technology companies can ban and regulate what they like and therefore have the power to control narratives and assist candidates to win elections if they decide. This is dangerous especially given these businesses are run as profit driven entities and not for the greater good of the community in a non-mandatory voting system. Moving Beyond Censorship: Fostering Dialogue and Civic Engagement

Some believe that instead of resorting to the archaic measure of censorship, alternative approaches should prioritise critical thinking and self censorship, and civic involvement. Mandatory voting offers one such alternative, as evidenced by its success in reducing polarisation and increasing political engagement in countries like Australia, where voter turnout consistently exceeds 90%19.

By implementing mandatory voting in the United States, this could diminish the influence of extremist groups, lessen political polarisation, and cultivate a more inclusive and representative democracy. Alongside mandatory voting, it is imperative to establish clear ethical standards for politicians which include consequences for breaking these standards. These standards would oblige politicians to uphold honesty, integrity, respect for diversity, and a commitment to the common good in their communication and decision making processes. By enforcing accountability and transparency, ethical standards can help restore trust in the democratic system and deter unethical behaviours such as disseminating misinformation or exploiting societal divisions for political gain.

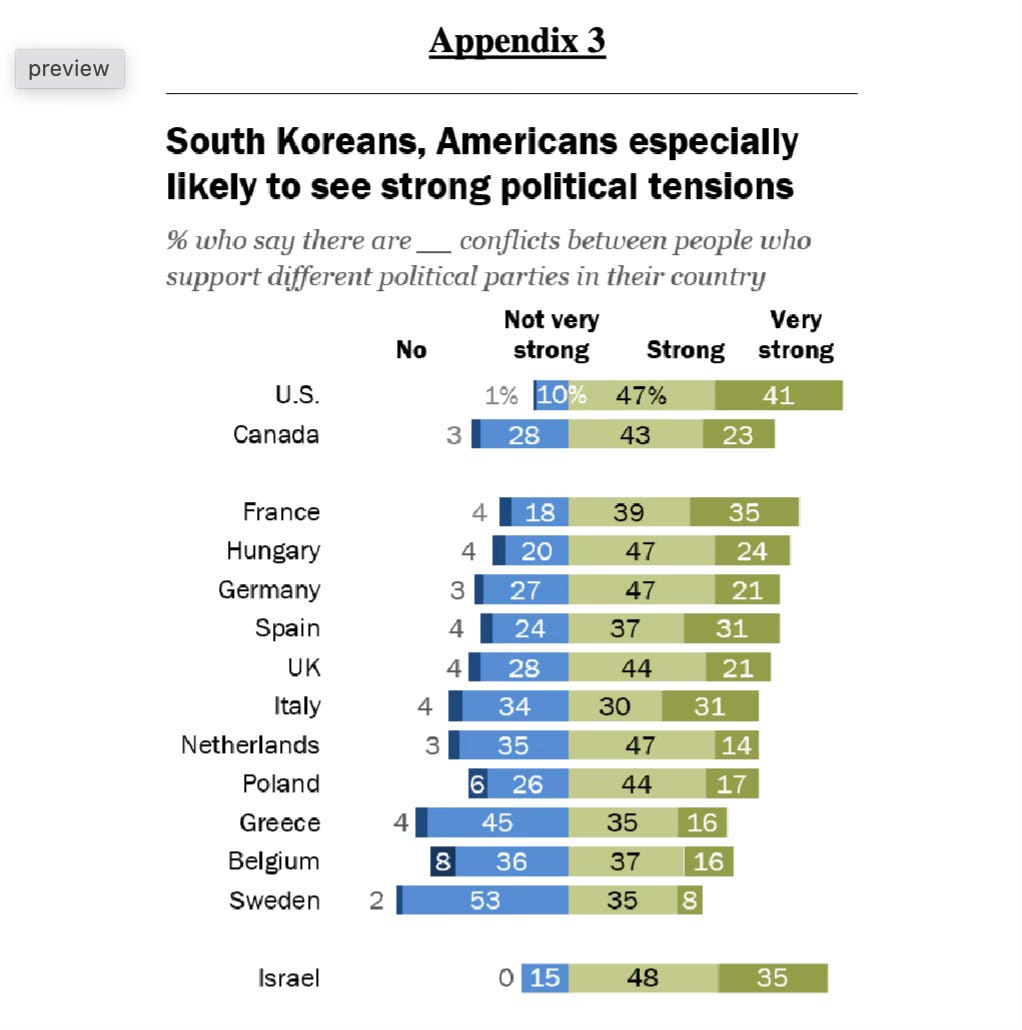

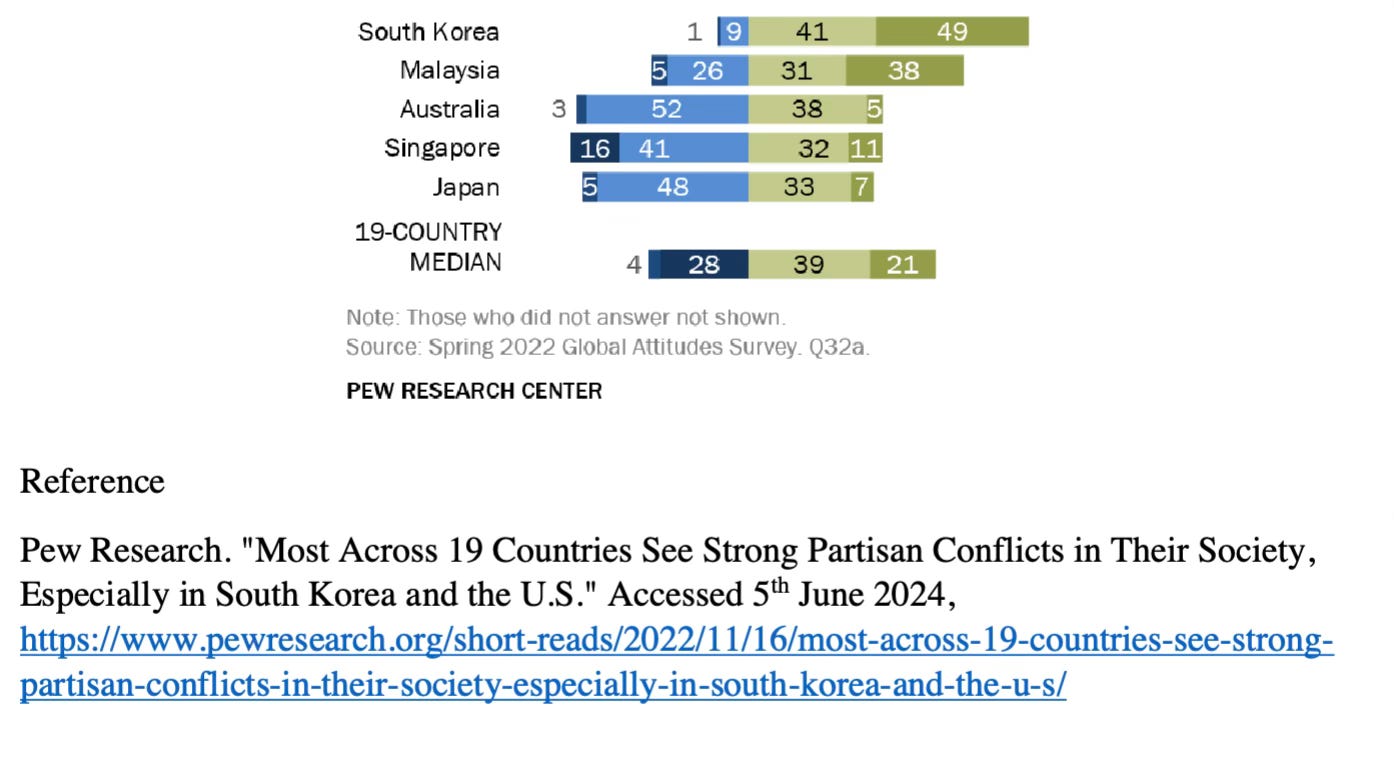

Censorship historically has failed each and every time it has been used. Thus, the USA must explore alternative strategies that promote dialogue, critical thinking, and civic engagement to change its culture. Further research can be done outside the scope of this report on other alternative solutions looking at other countries whose measures of political polarisation and misinformation are much lower than the USA, Appendix 3 shows a ranking of other countries

and their likelihood for political tension20.

In conclusion it is evident from this research paper that social media has significantly transformed political campaigning in the USA, enabling unprecedented levels of engagement and advocacy while intensifying political polarisation. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have revolutionised communication, making real time interaction and data

analytics essential in modern politics. This transformation has led to many changed outcomes including the organisation of mass scale grassroots movements whilst having negative consequences, including the spread of misinformation and increased ideological divides.

However, this research shows that political polarisation in the USA has been growing over the past few decades, reflecting deep ideological divisions among voters and impacting democratic processes and societal cohesion. It is clear that social media platforms have been used to amplified polarised discourse and unchecked misinformation for political gain, exacerbating this divide. Case studies, like Trump's use of misinformation in the 2021 election, highlight the real world extreme consequences, negatively impacting USA’s political culture.

To address these challenges, the USA must consider effective alternatives to censorship. Implementing mandatory voting and establishing ethical standards with repercussions for politicians can promote transparency, accountability, and evidence based discourse. These measures would empower citizens and restore trust in democratic institutions and the media.